In all the bloody legacies of the Tudor family, perhaps there is none quite so tragic as the death of sixteen year old Lady Jane Grey. Also known as the “Nine Days Queen” the shy reluctant Jane ruled England for exactly nine days before she was jailed and eventually executed.

Jane Grey was born on this day, October 13, 1537 in Bradgate Park, England. It was her great misfortune to have been born into a faction of the Tudor dynasty. Jane was the great-granddaughter of Henry VII through his younger daughter Mary. This made her first cousin once removed to King Edward VI, son of Henry VIII.

Sins of the Father

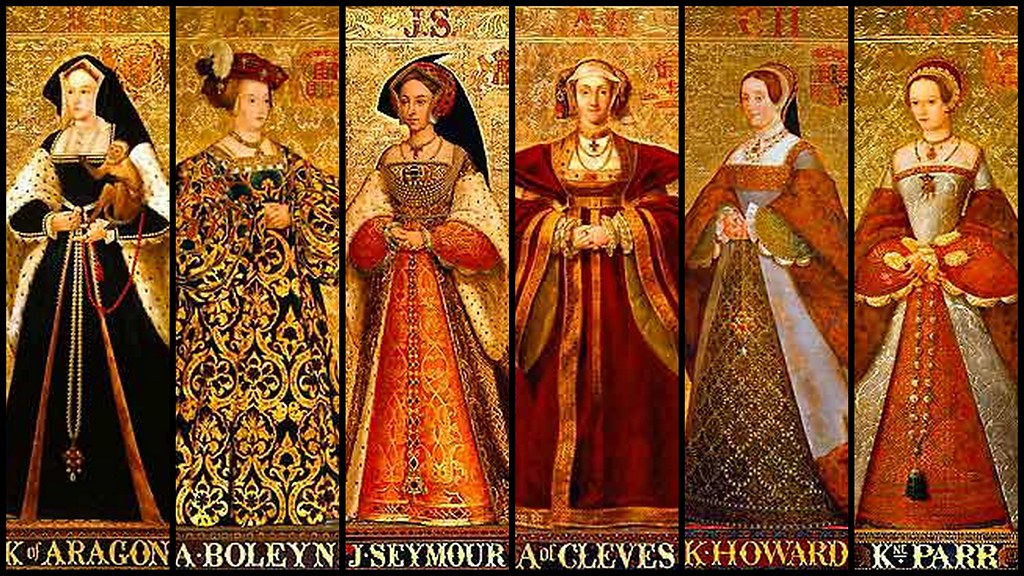

Those of you that know Tudor history might remember Henry VIII’s nearly impossible quest to bear a son. After blowing through two marriages, Henry finally wed queen’s maid Jane Seymour who bore him their son Edward. (Jane died in childbirth, and Henry blew through three more wives after her, but that is another story for another day.)

Little Prince Edward was a treasure to Henry, who treated him like a delicate doll, constantly in fear that his only son might fall ill and not continue the Tudor dynasty. Upon Henry’s death, the nine year old Edward took the throne. But alas. Henry’s darkest fear actually did come true. Edward only ruled a few years until he passed away at the tender age of fifteen.

Before he died, young Edward made some rather unconventional arrangements about his own succession. He chose his cousin Lady Jane Grey as the next queen.

Edward had two half sisters, Henry VIII’s daughters Mary and Elizabeth. Henry VIII had actually written a will that eldest daughter Mary should succeed Edward in the event he had no sons (which, at age fifteen he did NOT.) However, Mary was a Roman Catholic, and this did not sit well with young Edward, a strict Protestant.

On his deathbed, Edward wrote a new will. This will removed his half-sisters, Mary and Elizabeth, from the line of succession on account of their “illegitimacy”. It was probably pretty easy for Edward to declare his sisters illegitimate. They were the daughters of Catherine of Aragon and Anne Boleyn, respectively. Henry VIII had managed to annul, disintegrate and destroy those marriages, banishing Catherine and beheading Anne, in his frantic attempt to marry someone who could give him a son.

Overburdened

Young Jane was somewhat of a little pawn in a big game. When she was called to become queen, Jane was a timid, bookish teenager. She, like the rest of England, had no idea about the new will.

She had been given an excellent education and had a reputation as one of the most learned young women of her day. She was also married. In May 1553, Jane had been married off to Lord Guildford Dudley. He was a younger son of Edward’s chief minister John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland. The marriage had, no doubt, been arranged by John Dudley in his own hopes of advancement, knowing his new daughter in law had some chance of becoming queen.

Edward VI died on July 6, 1553. On July 9 Jane was informed that she was now queen. Still unsure of herself and her shaky claim to the throne, Jane accepted the crown with reluctance. She was moved to residence in the Tower of London, and on 10 July, she was officially proclaimed Queen of England, France and Ireland.

Cliques and Coups

Meanwhile, Mary Tudor got busy. As soon as Mary was sure of King Edward’s demise, she traveled to East Anglia, where she began to rally her Catholic supporters. In turn, John Dudley got some troops together to capture Mary. He was unsuccessful.

Mary had a lot of support from the English people. There were still many Catholic strongholds in the country and even Protestants backed Mary because they believed she was the rightful heir to the throne. In addition, another nobleman, one Henry Fitz -Alan, 19th Earl of Arundel, engineered a coup d’etat in Mary’s favor. Under pressure from the English people and other forces, the Privy Council switched their allegiance and proclaimed Mary as queen on July 19, 1553.

And that was the end of Jane. On that same day, she was imprisoned in the Tower’s Gentleman Gaoler’s apartments.

Her husband went to Beauchamp Tower. John Dudley, for his part, was executed on August 22, 1553. Jane — henceforth referred to as “Jane Dudley, wife of Guildford”, was charged with high treason. Her husband and two of his brothers were also charged. Their trial took place on November 13, 1553. All defendants were found guilty and sentenced to death. Jane’s guilt was evidenced by a number of documents she had signed as “Jane the Quene”.

Jane’s fate was to “be burned alive on Tower Hill or beheaded as the Queen pleases.” Burning was the traditional English punishment for treason committed by women.

To Burn or Not To Burn?

The decision seemed a bit harsh. Jane was so young. She was still beloved by many. She even seemed to have little to do with her own fate. The Imperial Ambassador began a petition in her favor, pleading to Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, that Jane’s life be spared. Even Queen Mary herself was reluctant to sign the death warrant. Some historians believe that if Jane would have agreed to accept Catholicism, she could have saved her own life and gained favor with Mary. However, during her imprisonment Jane remained a dedicated Protestant. She even wrote letters condemning the Catholic Mass, going so far as to call it a “Satanic and cannibalistic ritual.”

As she awaited her sentence, Jane’s family were busy scheming again.

In January, 1554, the “Wyatt Rebellion” began. This was a plan instigated by Thomas Wyatt the Younger to destroy Queen Mary’s reign. Jane’s father, Henry Grey, and two of her uncles joined the rebellion. Upon hearing this news, the government assumed they could never trust Jane. Mary then signed the death warrant for both Jane and her husband Guildford.

Her beheading was first scheduled for February 9 1554, but was then postponed for three days to give Jane another chance to convert to the Catholic faith. Mary sent her chaplain John Feckenham to Jane. Although Jane would not convert, she became friends with Feckenham and requested he accompany her to the scaffold.

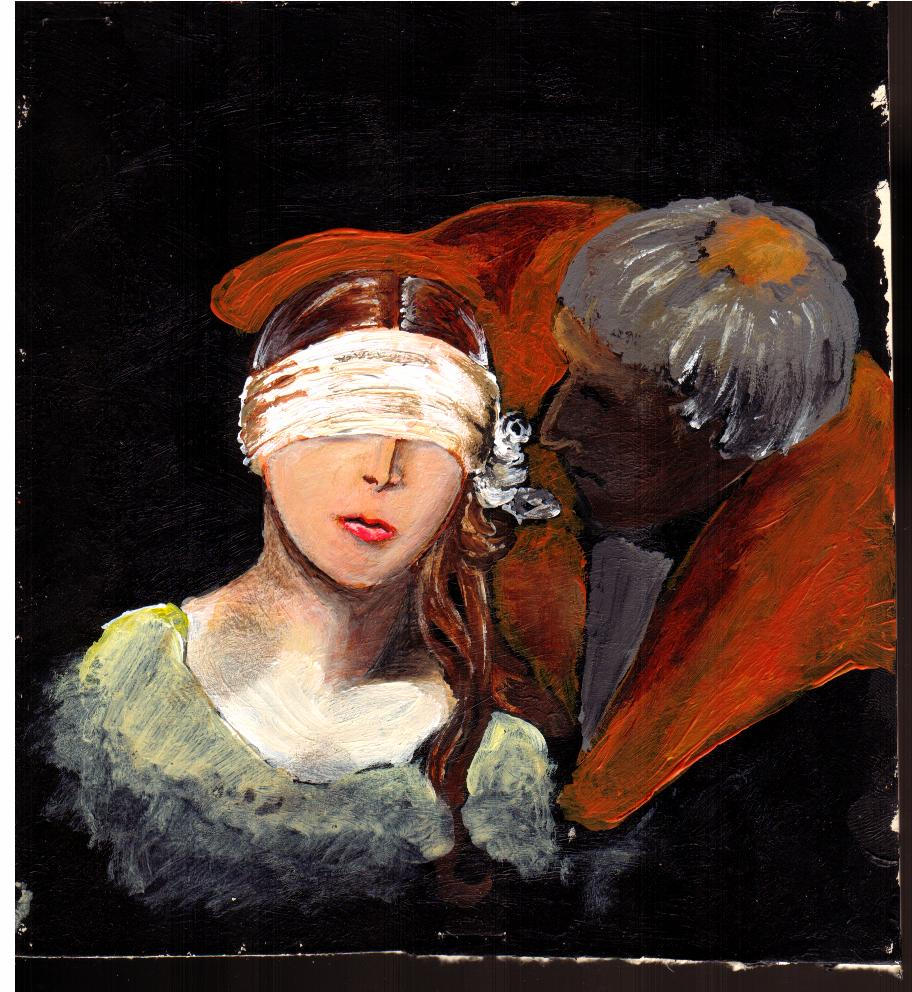

Blindfolded and Bewildered

Jane’s execution, with Feckenham by her side, is depicted in this famous painting by Paul Delaroche, 1833. No one knows for sure what Jane looked like, as she was the only Tudor monarch who never had a portrait done.

On the morning of February 12, the authorities took Guildford from his rooms at the Tower of London to the Tower Hill. Instead of a simple beheading, Guildford suffered the sadistic punishment of being drawn and quartered — a process in which the victim was kept alive while his entrails were cut out. A horse and cart brought his remains past the rooms where Jane was staying. Seeing her husband’s corpse return, Jane cried out: “Oh, Guildford, Guildford!”

She was then taken out to Tower Green for her own beheading. Jane gave this speech from the scaffold:

“Good People, I am come hither to die, and by a law I am condemned to the same. The fact, indeed, against the Queen’s highness was unlawful, and the consenting thereunto by me: but touching the procurement and desire thereof by me or on my behalf, I do wash my hands thereof in innocency, before God, and the face of you, good Christian people, this day.”

Jane’s wording should be noted. “… touching the procurement and desire thereof by me… I do wash my hands thereof in innocency…” It is a fancy, 16th century way of saying she never wanted the crown in the first place.

The executioner asked her forgiveness, which she granted him, pleading: “I pray you dispatch me quickly.” Interestingly, Jane then pointed to her own head and asked, “Will you take it off before I lay me down?” The axeman answered: “No, madam.” (Anne Boleyn’s executioner, a skilled swordsman, snuck up on Anne, behind her back, theoretically to soften the blow. So maybe Jane was just checking.)

She then blindfolded herself. But once blindfolded, Jane could not find the block with her hands, and cried, “What shall I do? Where is it?” Sir Thomas Brydges, the Deputy Lieutenant, helped her. With her head on the block, Jane spoke the last words: “Lord, into thy hands I commend my spirit!”

Jane and Guildford are buried in the Chapel of St Peter ad Vincula on the north side of Tower Green. No memorial stone was erected at their grave.

Lingering Legacy

Jane is gone but not forgotten. Her youth, the unfairness of her death and the sheer romanticism of her story have elevated her to an icon. Known as the “traitor-heroine” of the Protestant Reformation, she became viewed as a martyr. Jane was featured in the Book of Martyrs (Actes and Monuments of these Latter and Perillous Dayes) by John Foxe.

Jane’s story grew to legendary proportions in popular culture. She has been the subject of many novels, plays, operas, paintings, and films. One of the most popular was Trevor Nunn’s 1986 film “Lady Jane”. Helena Bonham Carter played the lead role.

Happy Birthday Jane. We hardly knew you.