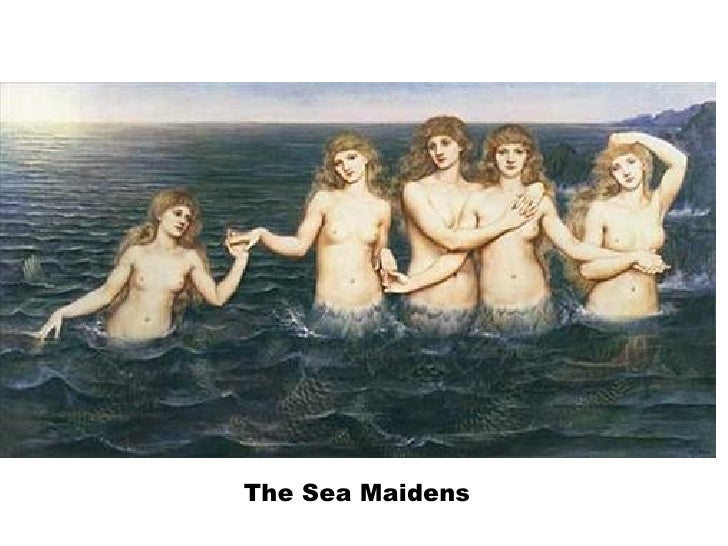

“I must be a mermaid… I have no fear of depths and a great fear of shallow living.”

―

“The mermaid is an archetypal image that represents a woman who is at ease in the great waters of life.” — Anita Johnson

“Mermaids don’t drown.” ―

The mermaid represents a woman’s physical and emotional depths. The Siren’s song, in mythology, was typically a thing to be feared, for sailors who followed it often ended up in a shipwreck. And yet, without these mesmerizing mythical creatures, our seas would be sadly lacking.

Mermaids not only weather the storm, they welcome it. Mermaids live in duality, embodying humanness along with a wild, animalistic and instinctual side. They are as changeable as the water itself, and yet they are ancient, a thing of complete and utter permanence.

How long have mermaids been around? Forever! Which is one reason why we should heed the wisdom of these divas from the deep.

The archetype of the mermaid has appeared in the folklore of every culture and people. They have popped up in the South Seas, the Greek Islands, the tundras of Siberia, the coasts of Africa and sun worshipping Scandinavia.

In Brazil, tribute is paid to the water goddess Yemoja. From Syrian legend came the Dea Syria, mother of all mermaids. Slavic cultures have tales of the Rusalka, water nymphs that can both harm and help humankind. Lithuanian folklore tells of Jurate, who lived in an amber palace beneath the Baltic Sea.

The far east also has no lack of mermaids. Korean mythology tells of Princess Hwang-Ok from an undersea kingdom of mermaids known as Naranda. There is also the tale of Kim Dam Ryeong, the Korean mayor of a seaside town, who once saved four hundred mermaids from being captured by fishermen. Chinese literature dating as far back as 4 B.C. speaks of mermaids who “wept tears that turned into pearls.”

Folklore from the British Isles is peppered with tales of mermaids. The Norman chapel of Durham Castle, built by Saxons, contains an artistic depiction of a mermaid that dates back to 1078. (One must wonder why busy Saxon masons would bother to etch a mermaid into the wall. They had cathedrals to build!)

In Cornwall, there is a legend of a mermaid who came to the village of Zenmor. There, she listened to the singing of a chorister named Matthew Trewhella. The two fell in love, and Matthew went with the mermaid to her home at Pendour Cove. Needless to say, he was never seen again. On summer nights, it is said the lovers can be heard singing together.

In 1493, Christopher Columbus reported seeing three mermaids near the Dominican Republic. Henry Hudson (of Hudson River fame) recorded in his captain’s log in 1608 that his crewmen had spotted a mermaid in the river. The sailors claimed that from the navel up “her back and breasts were like a woman’s” but when she dove under the water “they saw her tail, which was like the tail of a porpoise.”

In 1614, Captain John Smith (of Jamestown Colony and Pocahontas fame) recorded a mermaid sighting in his captain’s log. While sailing near the coast of Newfoundland, Smith wrote that he saw a woman “swimming with all possible grace.” He stated: “Her long green hair imparted to her an original character that was by no means unattractive.” (Green hair!) He also claimed “from below the stomach the woman gave way to the fish.”

Are mermaids real? Would these prominent men lie, and risk looking ridiculous in their logs?

A more recent mermaid sighting occurred in 2009. In the seaside town of Kiryat Yam, Israel, dozens of other people reported seeing the same astonishing sight: a mermaid frolicking in the waves near the shore.

A mermaid’s endeavors are not to be taken on by the shallow of heart. She moves in synchronicity with the ocean’s tides, rides the waves, rules the waters. The mermaid is passionate and generous, sometimes even granting wishes. Just don’t cross her; she can be deadly.

I hope summer finds you near an ocean, lake, pond or pool. (And if you happen to see one of these watery women, approach with caution.)

These beautiful portraits were done by contemporary Russian artist Victor Nizovtsev. Have a lovely, magical and mer-aculous day!