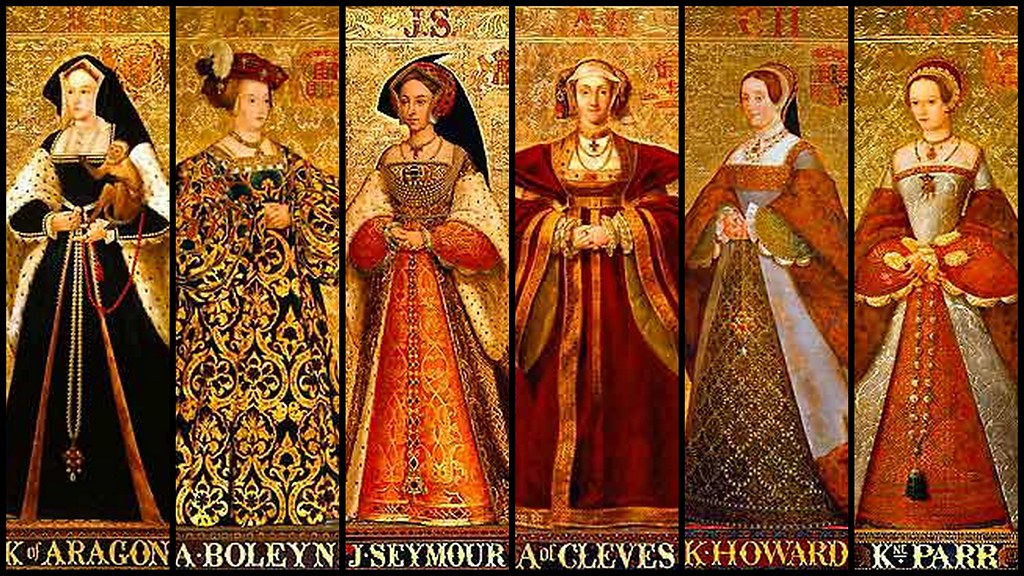

Ah those Medieval queens! They really had it rough — often serving as pawns in games of marriage, forced to breed like cattle, and fighting endless battles in their quests for a bit of recognition.

Consider Empress Matilda of England. Born on this day, February 7, 1102, Matilda led a chaotic life. But no one could call her irresponsible.

Matilda was part of a powerful blood line, daughter of Henry I of England and granddaughter of William of Normandy — aka “William the Conqueror”.

Almost as soon as she was out of the cradle, Matilda became a vehicle for marriage. She was betrothed at age 8 to Henry V, King of the Romans. Her father considered this an advantageous marriage, as Matilda would be uniting with a prestigious family line. She traveled to Germany where she was put under the custody of Bruno, Archbishop of Trier. Matilda was then educated in German language and customs, and declared Queen of the Romans. At the tender age of 12 she was married.

To make matters even more shocking, Henry was sixteen years older than her. So yes, we are talking about a 12 year old girl married to a 28 year old man.

Apparently, that sort of thing was normal in those days.

By age 14, Matilda was already running her own royal household, dealing with political conflict in Europe, sponsoring royal grants, conducting ceremonies and staking her claim as Empress of the Holy Roman Empire.

Things did not go well for Henry and Matilda. It seems Henry was a bit of a tyrant, constantly jailing his chancellors and subjects. This led to rebellions. Eventually, Pope Paschal II excommunicated Henry from the church of Rome. Henry and Matilda, however, were not so willing to take their punishment. They countered Paschal by marching over the Alps and arriving in Italy with their armies. Paschal ran away. His envoy, Antipope Gregory VIII, now under military pressure, agreed to crown Henry and Matilda at Saint Peter’s Basilica.

Weirdly, although Henry and Matilda were married for eleven years until he died in 1125, they never produced any children. This barren status was bad for Matilda. She was now a widow at age 23. With no offspring, she could never exercise a role as an imperial regent. This left her with two choices; either marry again or become a nun.

Meanwhile, back in England, trouble was brewing.

Matilda’s father Henry I, King of England, had only two legitimate children; Matilda and her brother William. (Ironically, Henry actually fathered 22 illegitimate children! But only William and Matilda had a claim to the throne.)

In 1120, William died in a shipwreck. This left Matilda as the only heir to the crown.

King Henry I still had hopes of bearing another legitimate son. His first wife had died, but he remarried. His plan failed and he sired no more children. Of course, the big dilemma now was finding another husband for Matilda.

Her father decided the best match for her would be Geoffrey of Anjou. This alliance would strengthen relations between England and Normandy. However, there were a few problems. Geoffrey was only 13 years old. Perhaps Matilda, having been exploited herself, was not keen on taking a child husband.

She had little choice in the matter. The couple were married on June 17, 1128. The newlyweds reportedly did not like each other very much. Matilda tried to get out of the union, leaving Normandy a several times. But Geoffrey always managed to force her back. Eventually, despite the fact that they were mismatched, they did have children. Their first son, Henry (yes another Henry!) was born in 1133.

King Henry I reportedly was delighted with his grandson Henry. King Henry I died in 1135. This brought about the precarious question of who would take the throne. Although Matilda should have been the legitimate heir, a man known as Stephen of Blois, Matilda’s cousin, and one of old Henry’s favorite nephews, staked his claim. Henry’s subjects had previously pledged themselves to Matilda, but many reneged on their pledge and followed Stephen. A woman had never ruled England before, and people did not take kindly to the idea. They apparently preferred a British male king to a female ruler with a foreign husband.

Matilda, however, was not willing to give up. She had supporters — including Robert of Gloucester and King David I of Scotland. They attempted to overthrow Stephen with armies from Normandy. So began the 19-year civil war known as The Anarchy.

Between 1138 and 1141, feuds between Matilda and Stephen put the country in chaos. In 1141, Matilda captured and imprisoned her cousin. She then began to make arrangements for her own coronation. However, it seems she still was unpopular with the people. Reportedly, Matilda imposed several taxes and placed sanctions upon her would-be subjects. The people revolted. Growing animosity weakened Matilda’s claims. Then, Stephen’s wife (ironically, also named Matilda!) counter attacked with her own army.

Side note: Yes, I am wondering why they insisted upon naming everyone Matilda and Henry.

- Henry I had at least one illegitimate daughter named Matilda.

- Stephen’s wife was named Matilda.

- The Empress Matilda’s mother was also Matilda, aka Matilda of Scotland.

- Eight rulers of England were named Henry.

- Five rulers of France were named Henry.

- Four rulers of Castile were named Henry.

- Six Holy Roman Emperors were named Henry.

- Seventeen Dukes of Bavaria were named Henry.

To be fair, I assume it had something to do with beliefs in the influence of names. The name Henry actually means “power” or “ruler”. Matilda means “mighty in battle.” Appropriate! 🙂

Queen Matilda (Stephen’s wife) eventually defeated Empress Matilda. Empress Matilda was forced to release her cousin from prison. Stephen was officially crowned King of England in 1141.

Although Empress Matilda attempted more war strategies, setting up forces at Devizes Castle and attempting to oust Stephen for several more years, she was ultimately unsuccessful. She returned to Normandy in 1148. Her husband Geoffrey died in 1151. After Geoffrey’s death, Matilda ruled Anjou. She also set about trying to establish her son Henry as King of England.

Young Henry brought his armies to England with the intention of overthrowing Stephen.

Ironically, Henry somehow became Stephen’s “adopted son” and successor! When Stephen died in 1154, Henry took the throne as King Henry II. Henry married Eleanor of Aquitaine, another powerful Medieval Queen.

Empress Matilda lived to the ripe old age of 65, probably a record for women of her day. She died on September 11, 1167. In yet another sad, ironic twist, her tomb stone only identifies her as “Daughter of King Henry, wife of King Henry and mother of King Henry.” (I guess they leave us to figure it out — Henry I of England, Henry V of Rome and Henry II of England, respectively.)

At any rate, Matilda remains a significant historical figure. Her battle with Stephen had a profound effect on politics of the time. Perhaps Matilda even paved the way for the many powerful queens that were eventually to rule England — Mary, Elizabeth I, Victoria and Elizabeth II.

Happy Birthday Empress Matilda! You put up a good fight.